Why Castle Rock Looks The Way It Does

The town’s government uses zoning to keep the suburb expensive and exclusive

Castle Rock is a suburban hellscape.

The residential parts of the town consist of rows upon rows of expensive houses that repeat just a few floor plans. The town’s businesses are mostly located in strip malls and shopping centers, the businesses themselves mere coastlines of the asphalt continents reserved for parking. For all practical purposes, you cannot get anywhere without a car. You could only call the town diverse if you were referring to the diversity of its fast-casual food franchises.

This situation did not arise naturally. It was planned and provided for by law. In Castle Rock and many American communities, local governments use zoning to keep communities expensive and exclusive.

The term “zoning” refers to laws that regulate how certain areas of land can be used. It makes sense to have some restrictions on what people can do with property. You wouldn’t want an airport built next to people’s houses, or a strip club built across from a kindergarten. Zoning often goes beyond common sense, though. Some local governments use it to shape every facet of life in a community.

Title 17 of Castle Rock’s town code is dedicated to zoning. The code contains extensive regulations on anything in the town you could imagine. For example, a building in a single-family residence district must be (obviously) a home for only one family. It must sit on a lot of at least 9,000 square feet, with a minimum 7-foot side yard and 25-foot front yard. If you wanted to turn your house into, say, a corner store, so that people could buy milk and eggs without having to drive to King Soopers, doing so would be illegal. What about turning a house into apartments with low rent? Think again, outlaw.

The zoning code also ensures that there will never, ever, so long as the Earth keeps turning, be a parking shortage in Castle Rock. The code establishes parking requirements for various types of businesses. Some examples: day care centers must have one space per employee plus one space per six children plus one space per facility-owned vehicle plus a passenger loading space. Supermarkets must have five spaces per 1,000 square feet of gross floor area. Mini-golf establishments require one space per hole plus half a space per employee. Veterinary hospitals require one space per employee plus one space per dog or cat and one-tenth of a space per snake. (The last sentence is made up.) According to M. Nolan Gray in The Atlantic, these parking minimums make building new housing or businesses more expensive and take up space that could be put to other uses.

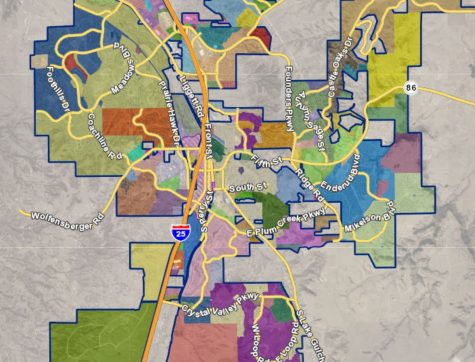

All these regulations can get confusing, so the town of Castle Rock has a color-coded map of the town’s zoning, which has so many lines and colors that it looks like a stained glass window. The Meadows neighborhood is split between two color codes. Upon clicking them, I found that the Meadows is not categorized under one of the categories specified in the town code, but instead is categorized under either the third amendment (67 pages) or the fourth amendment (77 pages) to that code. Among other things, these amendments regulate building height, land use, open space requirements, and the total number of residences in a given area.

Zoning anywhere, and especially in Castle Rock, is using the law to sculpt a community. Because local governments are democratic, the sculptors are the town’s residents. Castle Rock is a homeowners’ town: according to the Census Bureau, 78% of Castle Rock housing units are lived in by their owners (as opposed to renters.) Castle Rock is also 88% white, which I’m sure is entirely a coincidence. The town’s residents sculpt the town in their own interest: to keep housing expensive and to keep the town homogenous.

This is not a secret. The town’s official website says:

“Zoning code enforcement helps protect property values by ensuring development meets the Town’s zoning and land-use regulations. Our codes prohibit activities that would disrupt or change the nature of neighborhoods.”

This is a euphemism for “the people who live here want the houses they already own to be expensive, and they don’t want poor people moving in next to them.”

Zoning has harmful consequences. Homeowners’ use of zoning to increase property values excludes low-income people from places that the Center for American Progress calls “opportunity-rich areas” – places like Castle Rock with good jobs and good schools. According to M. Nolan Gray’s piece, zoning laws make it costly or straight-up illegal to build new affordable housing, which keeps rents high and contributes to the homelessness crisis; Gray points out that the one big city without zoning, Houston, is “one of the most affordable and diverse cities in the country.”

Zoning laws also perpetuate car dependence, making it illegal to build, for example, apartments within walking distance of stores, so that people could live and work without a car. This once again creates communities that favor the wealthy, as well as exacerbating noise, pollution, and climate change.

The point of suburbs has always been exclusion. Way back in 1968, a US government commission found that suburbs had their origins in white flight from cities with growing Black populations, and today, town governments in suburbs continue to use the force of law to keep their towns expensive and homogenous. We need to get rid of zoning to build a more inclusive American prosperity.

Nathan Lucas • Jan 19, 2023 at 8:44 am

I’ve always felt that such bland city design makes it so that it’s hard to “go outside.” The only reason anyone ever leaves their home is to go somewhere: grocery stores, school, work, etc. Hardly anyone ever leaves their home just to enjoy Castle Rock, since it’s so bland that there’s nowhere to enjoy it.

Great article, it really spoke to me 🙂

MD Tucker • Jan 18, 2023 at 12:42 pm

The authors comments, blaming zoning as the cause of lack of affordability for housing is considerably misplaced. The blame goes to inflation which is currently 10.5% for the last two years. And over the last 15 years housing prices have shot up, also due in part to inflation.

Inflation is the hidden tax which liberal governments impose upon its population. Conservatives, including libertarians, Republicans, independents, and constitutionalist have endeavored to keep the inflation rate at 2% annually. This allows for pay increases of 4 to 5% to counteract Inflation.

At 2% annual inflation, the government essentially reduces the value of a $100 bill to zero in 50 years. This is simplistic but useful. Similarly at 10.5% inflation annually, which we are now suffering, the government confiscates your $100 bill in approximately 10 years. Inflation, thanks to liberals, essentially is the cause of the lack of affordability for lower income folks.

The primary cause of exploding inflation is the excessive printing of money and dumping it into the economy. The price of housing and all other goods have essentially doubled or tripled as a consequence of inflation, not with standing supply and demand.

My home here in Castle Rock has doubled in value, i.e. inflationary/mobility forces. I can’t afford to move, nor do I wish to, but if I were to do so, I could not afford to buy the same home, because of the high inflation in price increases, which have nothing to do with the zoning. Not surprisingly, my taxes have also doubled in the same time. If I had to buy here in Castle Rock today, like you, I would be priced out of the market.

Much of the exploding real estate values are also due to another major factor. Mobility of the US population is another primary cause. Taxes in states like California and New York, etc. have become so exorbitant that people move to places where lower taxes exist. I did. Colorado used to be one of those and in particular, Castle Rock was quite affordable about 15 years ago. Mass migration of the US population has created the problem here in Castle Rock. In the state where I used to live, real estate was so expensive I chose to move, selling my 1,200 square foot house in the other state for $290,000. Liberals controlled that other state. Get the picture?

The first house I bought here in Castle Rock was 4,200 square feet & cost $250,000, quite affordable for an average income. That same house on that same date would cost $1 million in the state from where I migrated.

In this article, the author advocates eliminating zoning to equalize opportunity for lower income folks. When neighborhoods eliminate zoning, economic blight sets in. This blight creates huge drops in property values and in community services. So indeed, people who want the higher level of services, Home, values, and safety in their communities will indeed move out and move elsewhere where they can obtain those.

On the other hand, ignorance of these facts, promotes a communist agenda to “equalize”, without regard to merit and ability. All of us must guard against that, because freedom is not free.

Mitchell Davis • Jan 24, 2023 at 10:23 am

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. While it is true that government policy affects inflation and that inflation affects housing prices, this article is not about inflation. It’s about zoning. While the determinants of housing prices are complicated and numerous, the most fundamental is supply and demand, and zoning artificially constricts supply in high-demand areas. Houston has no zoning and they are doing quite well with affordability. Parking minimums, which are mentioned in the article, also drive up housing prices directly via increased construction costs. You would think that if we as a society value freedom, it shouldn’t be illegal to build an apartment block without a certain number of parking spots.

M Gordon • Jan 17, 2023 at 10:47 pm

The author of this article should get out a little more often. Clearly he hasn’t seen the apartments that have been built, and are being built in the Promenade area. Clearly, he hasn’t been downtown to see the Riverwalk apartment buildings that were built with the intention of the residents being able to walk to downtown businesses where they work, if they choose to do so. You sure did paint a bleak picture for for a town that continues to grow and provide opportunities to those that wish to live here. Hope this isn’t proof of what the education system is teaching the kids.

Devan Martin • Jan 16, 2023 at 11:59 am

Modern day red-lining

Mitchell Davis • Jan 17, 2023 at 9:08 am

I don’t think it’s quite as bad, but definitely in the same spirit